This story was originally published by Global Press Journal.

KAMPALA, UGANDA — Moses has been on the run. “Wherever I go, I am witch-

hunted after people discovered that I am a homosexual,” he says, his voice trembling.

Moses, who identifies as gay and chose to use only his first name for fear of retribution, had managed to keep his sexuality a secret for a long time. The 28-year- old is also a member of the Church of Uganda, which opposes homosexuality. Until June 2023, he worked as a cook in a school founded by the Church of Uganda in the eastern part of the country. (Global Press Journal is withholding the name of the school to protect his identity.)

Moses says his problems started in March 2023, after Uganda’s Parliament passed the anti-homosexuality bill — which President Yoweri Museveni later assented into law — criminalizing homosexuality and practices related to and in support of it. The law was supported by the archbishop of the Church of Uganda, the Most Rev. Stephen Samuel Kaziimba Mugalu.

The endorsement prompted a chain of reactions from the Anglican Communion, or churches with roots in the Church of England. One of them was from the archbishop of Canterbury, the Most Rev. Justin Welby, who is the most senior bishop in the Church of England. In June 2023, he criticized the Church of Uganda’s support for the law, citing it as contradictory to church principles, particularly the belief that every human being who is baptized and seeks to identify with the church has a right to belong there. In response, the Church of Uganda rejected the authority of the archbishop “as an Instrument of Communion” — that is, the leader of the Anglican Communion — for his support of LGBTQ+ believers.

While all this was happening, back in Moses’ hometown in Buikwe district, people started talking about his sexuality. Word spread fast. Then, in June 2023, Moses lost his job. “The head teacher and school board met and sacked me,” he says. “They said I am a threat to the community and the school.”

He says there was a likelihood of being lynched. He ran for his life and continues to do so today.

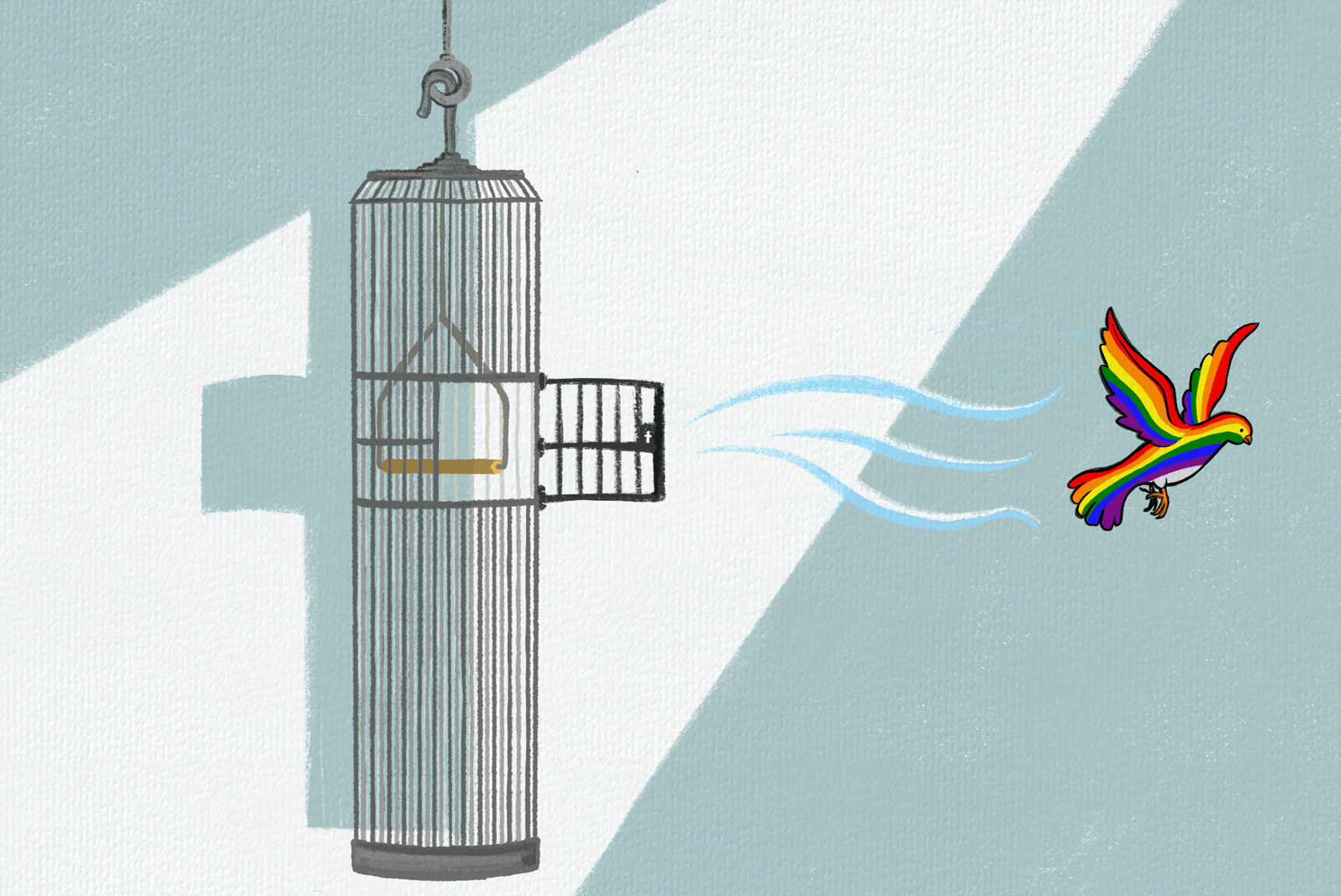

Like Moses, sexual and gender minorities who are congregants of the Church of Uganda say they face increased homophobia, fueled by the deepening schism between the Church of Uganda and its mother church, the Church of England, over Uganda’s homosexuality law. They say the situation has put their lives at risk and denied them a right to worship.

Kampala-based psychiatrist Hillary Irimaso says this kind of isolation can lead to feelings of dehumanization and ostracization, contributing to anxiety, depression and sleep disturbances.

In fact, a January report by Women of Faith in Action and Faithful Catholic Souls, with support from East Africa Sexual Rights and Health Initiative, shed light on how religious beliefs have contributed to intensified homophobia in the country. The study was based on interviews with 50 Kampala residents who identify as LGBTQ+ and were raised as Christians from various religious backgrounds, including Anglican, Catholic and Seventh-day Adventists, and found that they face feelings of isolation and depression due to the conflict between their sexual or gender identity and their religious teachings. Some said they grapple with religious trauma and have stopped identifying as Christian altogether.

An old rift

The Church of Uganda, which is a member of the Anglican Communion, was established in 1887 by missionaries of the Church Missionary Society from England. It became an autonomous province alongside Rwanda and Burundi in 1961, and a province on its own in 1980 with its own governing structure. Its congregants, called Anglicans, make up about 32% of Uganda’s population, second to Catholics, at 39%.

The rift between the Church of Uganda and the Canterbury Cathedral over sexuality isn’t new or unique to Uganda. Since the consecration of a gay bishop in the United States in 2003, there have been disagreements between Canterbury and other churches within the Anglican Communion over doctrine, says Chris Tuhirirwe, a senior lecturer of religious studies at Makerere University.

In fact, the Global Anglican Future Conference, which represents an estimated 85% of the Anglican Communion worldwide, formed in 2008 to oppose what they called“moral compromise” and “doctrinal error” within the Anglican Communion, including the move to embrace homosexuality.

At the 2023 GAFCON in Kigali, Rwanda’s capital, just over 1,300 delegates met and reaffirmed their loss of confidence in the archbishop of Canterbury and the instruments of communion led by him, adding that they could not “walk together” with him or those who had similarly strayed from church teachings.

Contradictory teachings

To the Rev. Canon William Ongeng, the provincial secretary of the Church of Uganda, the archbishop of Canterbury’s stance contradicts the church’s biblical teachings. “When your mother goes astray, much as you won’t beat her, you point out that what she is doing is wrong and refer to what she used to groom you and make you. So, we are resisting this contradiction because we were told that it is not godly for people of same sex to marry,” he says.

But Flavia Kyomukama, who advocates for the rights of marginalized peoples through the Ugandan nongovernmental organization Action Group for Health, Human Rights and HIV/AIDS, sees the Church of Uganda’s position as a failure to correctly interpret the Bible. As a child, she says she knew the church as the only place a person could seek solace if they were being persecuted.

“What exactly do they want them [LGBTQ+ people] to do, throw themselves in the lake?” she asks, adding that the Bible preaches reconciliation.

An administrator in the Church of Uganda, who agreed to speak to Global Press Journal on condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal, says that although he agrees the archbishop betrayed the Anglican Communion, he believes the Church of Uganda should welcome sexual and gender minorities instead of stigmatizing them.

Onen, 28, identifies as gay and prefers to go by his second name for fear of retribution. He says he’s Anglican but no longer feels comfortable in the community at St. John’s Church of Uganda, Kitintale, in Kampala, due to discrimination. “The gospel that is being preached on the pulpit these days is just meant to insult and belittle us, the LGBTQs. I used to go to church and pray but not anymore,” he says.

Onen says he stopped going to church in July 2023 after he was humiliated during a service.

“They pointed at me when we had gone for a conference in Mukono. We had been invited to share our experiences. I shared about my life and what I was going through given my sexual orientation and have since become an object of gossip. I left the congregation,” he says.

However, the youth mission coordinator at St. John’s Church, Emmanuel Arinaitwe, says that nobody has openly discussed their LGBTQ status within the church. “Maybe they left us because we are not leaning toward homosexuality,” he says.

Meanwhile, Onen says the Anglican Church has failed in its role of embracing people.

“It was in church where we used to get words of encouragement and feel strong. I miss the word. I used to learn a lot from church, but now I pray at home,” he says. However, this is not enough for him, he says, as he has no one to share encouragement with. He says he has suffered depression as a result.

Edna Namara is a Global Press Journal reporter based in Kampala, Uganda.

Apophia Agiresaasi is a Global Press Journal reporter based in Kampala, Uganda.

Global Press is an award-winning international news publication with more than 40

independent news bureaus across Africa, Asia and Latin America.

Uganda, which is part of the Anglican Communion, will lose nothing for severing its ties with the Church of England.)