As written by

MASIIWA RAGIES GUNDA (PhD)

INTRODUCTION

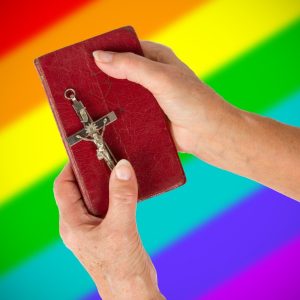

Nothing demands more care and caution when handling than the Bible! Nothing is more fragile than the Bible! Nothing is harder than the Bible! Nothing is as comforting and consoling as the Bible! Nothing is as inciteful and hate-inspiring as the Bible! I could go on, in short, the Bible is a library of paradoxes one time indicating left then turning right, another time accelerating in order to stop. There are not too many writings out there that can champion violence and peace in equal measure and yet that is what we are sometimes led to believe about the Bible. When handled recklessly, as has happened before in the history of humanity, the Bible can become a weapon of mass destruction, brutal, ruthless and efficient.

When handled with care and caution, the Bible can become an instrument of peace, stability, empowerment and sustainable love. The paradoxes of the Bible become more apparent when confronted with new socio-theological challenges and in our context one of such challenges revolves around the existence of ITLGB persons in our communities and churches. Sexual minorities are a reality in our communities from time immemorial, however, in the past few decades, sexual minorities have indicated their unwillingness to continue being forced to lead double lives: one for the family and another one for themselves.

The church and other institutions were quick to condemn and ostracize hence the initial reaction from most ITLGB was to move out of the church or to remain in the church without disclosing one’s sexual identity. A minority among the sexual minorities after serious reflections, meditation and prayers decided to “come out” as well as demanding their own space in the house of God. It is particularly because of this last group that we gather here to discuss about the violence that is visited on anyone, especially one in the minority with special focus on ITLGB persons. This presentation will try to show the manner in which the Bible has been used to entrench exclusionary and destructive attitudes towards sexual minorities while at the same time also showing how alternative readings can bring about constructive and inclusive transformation to our communities.

THE BIBLE IN AFRICAN CHRISTIANITY AND THEOLOGY

As theological educators on the African continent, we are aware that the Bible, the Quran and other Sacred Texts are highly regarded by their believers and sometimes even by non-believers. In fact, most African Christians understand themselves as “Bible-believing” and their churches as true reflections of “biblical Christianity” (Gunda, 2014). In understanding themselves as Bible-believing Christians, African Christians can be termed as fundamentalist in their self-evaluation. What are the implications of this fundamentalist approach to the Bible to the identity of the Church and the relationship between the heterosexual majority and the sexual minorities in the house of God? Further, we may also want to ask; what are the consequences of such an understanding, especially on sexual minorities?

While African exposure to the Hebrew Bible happened even before the time of Jesus Christ, it is true that this exposure occurred in North Africa and was largely limited to that region. Most of Sub-Saharan Africa was exposed first not to the Hebrew Bible but rather to the Christian Bible through the agency of Imperial Europe and Western missionaries. Our Christianity is, therefore, intrinsically connected to colonialism and all its vagaries and the quest for independence and the joys and sorrows of such aspirations. Our Christianity is essentially “Bible-based Christianity” (Gunda 2014) with the Bible being “the book; read in times of joys and in times of sorrows” (Togarasei 2008:73); in most cases the only piece of literature that one finds in many homes. The Bible was mediated to us as the Holy Book, one that saw everything that we did in our lives. Through this Book, we were informed that God spoke to us. We believed and we became “people of the Bible”, people who are quick to seek authentication from the Bible. While initially, the Bible was read to us, through the agency of missionaries and their indigenous collaborators, the Bible was translated into indigenous languages, thereby making it accessible to more people. The success of the translation project was aided by the success of the Mission schools that were set up by missionaries (Gunda 2009:79).

According to influential retired Nigerian Anglican primate Peter Akinola, ‘the primary presupposition’ of ‘bible-believing Christians’ is a high view of Scripture as inerrant and a sufficient guide in all matters of faith and conduct, such that its ethics and injunctions are of timeless relevance… ‘I didn’t write the Bible. It’s part of our Christian heritage. It tells us what to do’ (Boesak, 2011). To put it in simple terms, many African Christians consider the Bible to be without mistakes and that it is the manual for faith and conduct of all Christians in all generations. This best sums up the fundamentalist view of the Bible by many African Christians.

However,this perspective fails to appreciate the fact that the Bible houses “contesting voices” on various issues, including gender and sexuality. While most of us fully appreciate the concept of gender, that of sexuality remains a grey area. One’s sexual identity or sexuality is defined in terms of who is the object of our quest for intimacy and intimate relationship, hence heterosexuality for those who are attracted to members of the opposite sex, bisexuality for those attracted to members of both sexes, homosexuality for those attracted to members of the same sex, asexuality for those who are not attracted to any other person. These distinctions are normal and appear among human beings as well as other created animals. Understood in the way articulated by Akinola, “privileged prejudices” can easily become entrenched as “sacred”, as the powerful sponsor those parts of the Bible they read in support of their own entrenched positions. Since the Church has modelled itself on heteronormative lines and has largely adopted the understanding of sexuality from mainstream society, it is no wonder that the Bible has been deployed as an instrument that confuses sex and gender (Gunda, 2011, S. 96), to the benefit of the heteronormative ideology.

THE BIBLE: A SITE OF STRUGGLE

In the steps towards challenging the prejudices (race, gender, sexuality, ethnic, spirituality etc) that are so prevalent in our churches, we must begin by acknowledging the fact that the Bible is a site for struggle, that the ancient Israelites, early Christians and ourselves must always struggle with the text in order to hear the voice of God. There “is the struggle within the Scriptures themselves to find and hear the ‘voice of God’. Where, for instance, does one hear the voice of God on the question of war? In the chilling instruction from God to Israel in the herem, the ‘holy war’ instruction, to ‘utterly destroy’ Israel’s enemies (Deut.7:1-2; 20:16-18) or do we hear the voice of God in the words of the prophet Isaiah who stridently denounces even the idea that security is to be found in military strength and military alliances (Isa.31:1-5)? Where is God’s word: in the annihilation of one’s enemies or in Jesus’ injunction to love the enemy?”(Boesak, 2011).

What is observable from the fundamentalist approach is an attempt to wish away the multiple voices in the Bible by promoting only one voice without properly engaging the other voices. The Church and us, as Theological Educators, have a responsibility to discern the voice of God from the multiple voices that are heard in the Bible. To that end, we concur with Schussler-Fiorenza that “biblical interpreters have an ethical responsibility to consider the actual consequences of their interpretations”(Fiorenza, 1988). Since most readers read with a bias, each time a single text is read by many, it leads to the development of many interpretations, some of them even contradictory. “According to Patte, multiple interpretations are to be celebrated but not all of them are equally valid or plausible because some might be harmful or even dangerous to others in another context” (Kim, 2013, S. 2). Readings that will potentially incite hatred, violence and murder are against the essence of the transformation that the Church stands for, because the image of God in all human beings must be protected not threatened.

The shift from having the Bible read for them to indigenous people reading the Bible for themselves brought to the fore the nature of the Bible as a “site of struggle” on the African continent.During the colonial-evangelization onslaught and before the colonized-converted could read the Bible for themselves, the Bible was presented as a single unified document with a single unified voice on all matters, hence all who heard the text read were obliged to obey and follow its instructions. This was the period when slavery of the blacks was considered biblical, exploitation of blacks in their own homelands was presented as doing God’s work, being a good black was being obedient to the master. During this period, one could not refer to the Bible as a site of struggle, for there was no such struggle because the Bible was being read by one for the other, from the single perspective of the one reading.

Contestation becomes a reality once those being pushed outside resolve to put their own questions to the text and to wear their own reading glasses because it is only then that it becomes apparent to them and others that it is not necessarily the text that is pushing them outside, but the prejudice of the dominant readers (Gunda 2009). Africans, upon reading the Bible for themselves started encountering a God, who did not tolerate oppression and exploitation of one by another. They found a God, who did not behave the way the white masters behaved! They started realizing that there was nothing wrong with God but there was everything wrong with those that had presented God as their own image. At no point, must we ever resolve to engage the text in a struggle for understanding for the sake of understanding but for the sake of transforming our conduct.We should be suspicious when those in charge of empire are informing us how we should read the Bible and who we should accept in the house of God, for then the house of God will become house of Empire.

DOMINANT APPROACHES TO THE BIBLE: SHUTTING DOORS, INCITING VIOLENCE

Since the 1990s, the same scenario that characterised the colonial-evangelization context re-appeared in most communities in Southern Africa, with most Christians reading the Bible for people on the margins sexually, the ITLGB persons (As we have heard from earlier presentations, the Bible was used mainly as a tool to emasculate, dehumanise and disempower those on the margins). While these readings gained momentum in the 1990s, they remain the major voice on the subject and it was so vicious at first that those on the margins reacted in the same way that most Africans reacted towards the Western missionaries once they had fully appreciated how the Bible was being used to emasculate them: the ones emasculated reacted by disowning and removing themselves from submitting to this text! The text was labelled “empire text, developed and deployed for the benefit of only those that serve the empire while depriving those on the margins of empire!” (Rieger 2007). Sexual minorities have been labeled as “worse than dogs and pigs”, they have been labeled “sodomites who seek to have sex in public”, they have been labeled as a “threat to the survival of the human race” and an “abomination” that has been imported from the West.

One of the dominant ways of reading the Bible in addressing sexual minorities in Africa is “Selective literalism” in African theology and biblical studies that allows the Bible to be used as an instrument serving the interests of those who consider themselves authorized interpreters. Even though, most Christians will publicly proclaim that the Bible has “one voice” this single voice is not built on a reading of the entire Bible but on a reading of selected parts of the Bible. The parts so selected are mostly read literally, punctuated by the oft used statement of justification; “The Bible says…” What is written is taken at face value! This explains why texts such as Genesis 19, Leviticus 18 and 20, Romans 1, 1 Corinthians 6 and 1 Timothy 1 become so popular among African Christians on the subject of sexual minorities. These texts are read literally, disregarding their own contexts. Different denominations tend to focus on particular portions of Scripture, this selectivity is what we refer to here as “selective literalism”.

The second dominant way of reading biblical texts is the “Historical reading of etiologies and folktales”, which has led to misinterpretation and misappropriation of particular texts for contexts that are fundamentally different from the historical context and function of the etiologies and folktales. Not all biblical narratives have historical value in their context, in fact, most biblical narratives are etiologies and folktales, meaning their proper appropriation must acknowledge this fact. Appreciating that narratives are etiologies or folktales, does not in any way undermine their value because we grew up being taught fundamental lessons of life through such narratives. Reading them as history, however, create false analogies with our historical setting and experience. This is the dominant approach to the creation and fall narratives in Genesis 1-3, which have been used as the basis for rejecting the humanity of sexual minorities in our communities and churches.

These approaches to the Bible have been punctuated by a hermeneutic of rehabilitation of African culture and identity, which borders on a post-colonial approach. African theologians, Christians and leaders in general have approached the Bible with a desire to rehabilitate our damaged African identity. Most prominent in driving this perspective have been our political and religious leaders who have successfully, to a certain extent, in dividing the World into the wicked and evil West versus the holy and righteous Africa. From this perspective, sexual minorities have been labeled “a foreign import”, “gays for money”, “homosexuality is unAfrican” and so many other designations that suggests Africa is too holy to accommodate the entire range of human sexuality.

The African continent has seen also an intensive use of the blackmail and self-preservation hermeneutics against those that speak sympathetically and empathetically for and with sexual minorities. I know a lot of Bishops, theologians and prominent individuals who privately believe sexual minorities are victims of our prejudices but who do not dare to share their deepest thoughts and ideas on sexual minorities for fear of being labeled “one of them” and for fear that “their source of livelihood (congregants, customers etc) would be taken away from them”. The Bible is invoked to show how wrong people like Desmond Tutu are with the threat that those that follow him are on a highway to Hell. In short, some of us are blackmailed into silence for fear of the consequences to their own livelihoods.

These approaches have allowed most Christians to incite violence against sexual minorities and to exclude sexual minorities from the house of God. Doors have been closed for most sexual minorities, many have lost hope of ever stepping into the house of God and others have lost their lives because of a sermon! A few texts have been selectively chosen and read to entrench and sustain prejudices against those on the margins.

ALTERNATIVE APPROACHES TO THE BIBLE: OPENING DOORS, PLANTING LOVE

While we acknowledge the dominant ways the Bible has been approached in our context, that does not mean there are no other ways of approaching the Bible. Great strides have been made by scholars who have followed historical critical and critical contextual Bible studies. Two critical aspects need our attention from these approaches: they both engage with “context”, “context that produced the text of the Bible”, “context that is created by the text, literary context” and “context of the people that are reading the Bible” these are the contexts that Gerald West (1995:54-55) has labeled as the context “behind, in and in front of” the text. This approach has residues of Western historicism, which many scholars on the other side label as unAfrican, yet when we follow the path of West, Musa Dube, Allan Boesak, Desmond Tutu and others, we will realise that there is so much that can transform our African theologies to be more responsive to socio-theological challenges that keep on confronting the Church.

The approaches above have been accompanied by several hermeneutical principles but I will highlight liberation and transformative hermeneutics as critical in driving our work. Our preference for readings that promote liberation, justice and gender-equality is motivated by a realization that when closely considered, there is a clear and consistent strand in the Bible running through both Old Testament and New Testament. A strand that privileges liberation and justice for all can clearly be discerned in the Bible and I argue that these concerns are at the heart of God’s project with Israel. According to Allan Boesak, “At issue is also the question: what is the consistent message of the Bible? What is it that Jesus takes as the heart of his message for and of his activity in the world? There is a reason why Jesus announces his work in the world with the text from Isaiah 61… That is because … The sustained message of the Bible, repeated and deepened by the prophetic strain in the Psalms and the prophets, and given eternal weight by Jesus of Nazareth is God’s good news to the poor, God’s eternal commitment to justice, liberation and inclusion” (Boesak, 2011, S. 14).

As observed by Musa Dube, Luke 18:1-8 features Jesus telling a parable about persistent prayer to his disciples… one is struck that persistent prayer is equated with action-oriented search for justice. Persistent prayer is not a passive and private affair that we do behind our closed doors, nor is it tolerant of injustice. Rather persistent prayer is the a luta continua (the struggle that continues) act of insisting and working for the establishment of justice. Persistent prayer is, therefore, the refusal to live in oppression and exploitation until justice is established (Dube, 2004, S. 3).

Coming to the Bible and following on earlier observations that the Bible must be taken as a “site of struggle”, it is important to consider how we approach the Bible, especially being aware that some of our readings may cause death and harm while others may give life, comfort and security to some people. I consider the following points to be critical for our engagement with the Bible:

- That in the Old Testament, God’s Israelite project is to create a society that is governed on the principles of justice, righteousness, equality and equity. In this society, all would be welcome and would be catered for (the image of Eden, the Abrahamic nation (Gen.18), the Promise to the Exodus party, the Occupation and Settlement in the Promised Land and the reigns of Judges are all inter-woven into this project of God). The prophetic theology of the Old Testament is also falling into this consistent strand of thought that God is making Israel «a pilot project for just human society»

- The great inaugural statement by Jesus in Luke 4 follows this consistent strand of thought, proclaiming the «good news», which would offer hope, comfort and security to those who were at the mercy of the Roman empire. Are we surprised, then, that from its inception Christianity started off by becoming a refuge to those that were outcasts of their time and of their empire (the women, slaves, lowly gentiles)?

The second hermeneutical principle that we have found very helpful in advancing the inclusion of all, including sexual minorities in the house of God is “transformative hermeneutics” (Nadar). The reason why we read the Bible is because we consider it to be an instrument of transformation, it helps us to transform ourselves and others in our communities. It is therefore pertinent to always ask ourselves when we use the Bible, “what kind of transformation will result in this reading of the text?” Are we reading the Bible in a way that transforms men and women and those in between to become life-giving or life-taking individuals? Whatever our response to this question is, we can then ask again, “how is this transformation related to the central strand of voice that privileges justice and liberation in the Bible?” Any reading of the Bible that results in transformation, which is contrary to the tenets of justice and liberation cannot be celebrated as in sync with the voice of God. The truth of the matter is that unless handled with care, the Bible can easily become a weapon of exclusion and violence against those designated as sub-human, however, when read through the lense of justice and transformation, the Bible can become an instrument of hope, inclusion and love.

One way, that we have found useful in addressing the dangers of abusing the Bible in communities is through the Contextual Bible Study (CBS) in communities. The CBS is structured in such a way that it tackles head on the issues of justice, injustice, inclusion, exclusion and transformation of persons and communities. Clearly, justice, inclusion and transformation will come a result of struggles that we engage in. In search of justice, inclusion and transformation, the proverbial “sitting on the fence” does and has never worked because it is an act of co-option by the status quo. In articulating the values of the Contextual Bible Study method, Gerald West (2013) says;

- the CBS works with ‘struggle’ as a key socio-theological concept because ‘struggle’ is a key characteristic of reality. In that regard, the CBS takes sides with the God of life against the idols of death. For CBS the primary ‘terrain’ of struggle is the ideological and theological; CBS recognises that the Bible is itself contested, including biblical ‘voices’ or theologies that bring life and biblical ‘voices’ or theologies that bring death. Therefore, CBS ‘wrestles’ with the biblical text to bring forth life.

That is our challenge as theological educators, to act and teach in a way that «bring forth life».

CONCLUSION

There are women and of late, sexual minorities, whose lives have been severely threatened or cut short as a consequence of certain biblical interpretations. One life lost, is one life too many hence any approach to the Bible that threatens life must of necessity be challenged. This transformation of the Bible into a killing machine is regrettable because it can easily become the manual of peace, justice, inclusion and positive transformation of society into a society that accommodates all even celebrating the diversity that is inherent in all of us.

I am aware that this consistent strand has been threatened, challenged and over time been subordinated to empire strands that are also fairly represented in the Bible, especially, in the Old Testament but also in the New Testament. The project of God towards a just society, is disrupted when, instead of the other nations coming to copy the good thing in Israel, it was Israel who opted to be co-opted into Empire (Gen.18:18-19;1 Sam.8:5). Clearly, the Bible demands that we choose either to follow the first strand, which focuses on justice and righteousness or the reading that legitimizes injustice in society.

When it comes to those on the margins, let us always consider the question posed by Gerald West (2016); “On which side would Jesus err – exclusion or inclusion?”

REFERENCES

Dube, M. W. (2004). Grant me Justice: Towards Gender-sensitive multi-sectoral HIV/AIDS Readings of the Bible. In M. W. Dube, & M. Kanyoro, Grant Me Justice! HIV/AIDS & Gender Readings of the Bible (pp. 3-24). Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications.

Boesak, A. A. (2011). “Founded on the Holy Bible…” A Bible-believing Judge and the ‘Sin’ of Same-sex Relationships. Journal of Gender and Religion in Africa, Volume 17 Number 2, 5-23.

Rieger, J. Christ and Empire: From Paul to Postcolonial Times, Minneapolis: FortressPress, 2007.

Gunda, Masiiwa Ragies, “Homosexuality and the Bible in Zimbabwe Contested Ownership and Interpretation of an” Absolute Book” in Joachim Kuegler & Ulrike Bechmann (eds), Biblische Religionskritik: Kritik in, an und mit biblischen Texten – Beiträge des IBS 2007 in Vierzehnheiligen, Münster: LIT Verlag, 2009, 76-94.

West, Gerald O. “Reading the Bible with the marginalised: The value/s of contextual Bible reading” in Stellenbosch Theological Journal Vol 1, No 2, 2015, 235–261, http://ojs.reformedjournals.co.za/index.php/stj/article/view/1259/1774 accessed 28/08/2016.

Kim, Y. S. (2013). A Transformative Reading of the Bible: Explorations of Holistic Human Transformation. Eugene: Cascade Books.

Fiorenza, E. S. (1988). The Ethics of Biblical Interpretation: Decentering Biblical Scholarship. Journal of Biblical Literature 107, 3-17.

Gunda, M. R. (2011). Gender Prejudice in the use of Biblical Texts against Same-sex Relationships in Zimbabwe. Journal of Gender and Religion in Africa Vol 17 No 2, 93-108.

Gunda, M. R. (2014). African “Biblical” Christianity: Understanding the “Spirit-type” African Initiated Churches in Zimbabwe. In E. Chitando, M. R. Gunda, & J. Kuegler, Multiplying in the Spirit: African Initiated Churches in Zimbabwe ERA Volume 1 (pp. 145-160). Bamberg: University of Bamberg Press.

Togarasei, L. (2008), “Fighting HIV and AIDS with the Bible: Towards HIV and AIDS Biblical Criticism” in Ezra Chitando (ed), Mainstreaming HIV and AIDS in Theological Education: Experiences and Explorations, Geneva: WCC Publications, 71-84.

West, Gerald (1995), Biblical Hermeneutics of Liberation: Modes of Reading the Bible in the South African Context, Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications.

West, Gerald, Van der Walt, Charlene &Kaoma, Kapya, (2016),“When faith does violence: re-imagining engagement between churches and LGBTI groups on homophobia in Africa” The Other Foundation, http://theotherfoundation.org/htcia/

Nadar, Sarojini (2009), “Beyond the “ordinary reader” and the “invisible intellectual”: Shifting Contextual Bible Study from Liberation Discourse to Liberation Pedagogy” in OTE 22/2, 384-403.